As most of you are probably aware, there has been mounting tension between Russia, Ukraine, the the west (the United States and much of Europe) that has, as of writing this, resulted in Russia invading the Donbas in eastern Ukraine. I call it an invasion, rather than the propaganda term “peacekeeping” because an invasion is what it is. But it’s a fraught situation with many competing interests.

I tend to try avoiding the ‘news of the day’ type stories on my blog unless I can relate it to some bigger ideas. The Russia/Ukraine situation, however, is a bit more than just news of the day. There is the obvious fact that it could result in anything between a new Cold War between Russia and the west all the way up to a nuclear exchange. Such a situation ranks higher than Trump’s ongoing legal trouble or Biden’s most recent senior moment.

As with pretty much everything in Europe, the history of Ukraine is long and complex. Most of it was in the Russian Empire (the western edge being within the Austrian (and later Austro-Hungarian) Empire) between the 17th century and up until the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk during World War 1. After the war Ukraine declared itself an independent republic, but it found itself fraught with war against its neighbors and political strife, and in 1921 was turned into a Soviet puppet state. Ukraine suffered terribly under Stalin, for instance experiencing a massive famine known as the Holodomor, and then suffered yet more during Nazi occupation, only to once again become a Soviet puppet state after the Red Army retook Ukraine in 1943 and 1944 offensives. There it would stay until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, when Ukraine became an independent republic. It wasn’t all sunshine and roses for Ukraine after that, with a struggling economy and constant Russian meddling. In 2013-2014 protests and riots in Ukraine resulted in Russia occupying Crimea and pro-Russian forces (along with Russian help) occupying eastern Ukraine.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, despite promises to the contrary, NATO has expanded eastward, toward Russia’s western border. Vladimir Putin, who took office in 2000 (and has gone back and forth between president and prime minister as a loophole for Russian term limits) has decried the NATO expansion and weapons going into countries so close to Russia.

Opinions abound on what Russia, Ukraine, and the west ought to do about this situation. As in much of international relations, there tends to be two overarching ways of viewing a problem: the idealist driven view and the realpolitik view. The former is exemplified by the Wilsonian idea of “making the world safe for democracy.” The foreign policy of George W. Bush was (at least couched in) this sort of idealism: that the U.S. would spread democracy and liberal values to places like Iraq and Afghanistan, that the U.S. would be greeted as liberators by people happy to be out from under the heel of dictators and theocratic thugs, and that the success in these places would see democracy and liberal values spread all throughout the Middle East (never mind the U.S. staying cozy with other authoritarians like the Saudis and Turkmenistan, which is much more realpolitik).

Realpolitik, on the other hand, is what people mean when they talk about a country’s “interests.” This can be anything from protecting trade (or extraction) of tangible goods, such as oil, to national security, such as protecting borders, exercising influence over surrounding nations, and coercing “rogue” nations, and up to ideas of looking strong in front of adversaries by displaying military might and issuing sanctions. In realpolitik, a country does what needs to be done to protect interests, even if they have to act inconsistently, dishonestly, or in ways that cause harm (e.g. think of the U.S. backing coups in Latin American countries and in Iran during the Cold War, or the Vietnam War, or arming Afghan mujahideen during the Soviet-Afghan war).

Realpolitik can be exemplified in the Thucydides quote: “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” In other words, if you are a great power, like the U.S. or Russia or China, you do the kinds of things you would denounce anyone else for doing, yet everyone else has to live with it because what can they really do about it?

So, with Ukraine, the idealist position would be something like this: Russia should not be allowed to infringe on Ukraine’s sovereignty. If Ukraine wants to join NATO, that is their right as a sovereign nation. Being next to Russia does not give Russia the right to meddle in Ukrainian policy. It’s the people of Ukraine who ought to be in charge of their own destiny.

The realpolitik position for Russia would be this: Russia has an interest in meddling in Ukraine’s policies in order to keep its “sphere of influence” safe and under control (where sphere of influence is a very realpolitik concept). Russia also has an interest in making itself look powerful for both national security reasons and for reasons of wanting to be among the strong doing what they can crowd.

Putin has been trying to clothe his motivations in idealism, frequently talking about the historical, cultural, and religious connections that Russia shares with Ukraine, such as their ethno-linguistic history and Kiev being the place where Russian Eastern Orthodoxy began. This isn’t uncommon. Especially since World War 1 (the war that sullied the sort of Louis XIV / Frederick the Great / Metternich / Bismarck styles of great power politics that had been popular in Europe prior to 1914) countries have attempted to couch their motivations in a veil of Wilsonian-esque idealism, even if their true motivations are realpolitik.

Europe clearly has national security issues in mind when it comes to relations with Russia and how to handle the current crisis. They get a significant amount of their gas from Russia, and they are much closer to Russia (in range of medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles).

The United States has no such interests. Ukraine is not a treaty ally (yet) and there is much less trade between the U.S., Ukraine, and Russia than between Europe, Ukraine, and Russia. Ukraine is also not strategically that important to the U.S. (I’m sure people could come up with an argument as to why it is, but it’s certainly not vital). This is why the U.S. has couched much of its rhetoric on this in the idealism of Ukraine being a sovereign nation and that it is wrong for Russia to meddle in their affairs.

There is an argument to be made for the U.S. being involved in the conflict for realpolitik reasons. It’s the one that neoconservatives often invoke: to display resolve. In other words, to throw its weight around and show others, like Russia and China, that they are still a militarily powerful nation and that they are willing to use that military power to back up their demands. Should the U.S. make demands for Russia to stay out of Ukraine and then sit by while Russia invades Ukraine, it makes the U.S. appear weak and unable to back up what it says. It makes Russia and other nations not take its demands seriously. If the U.S. doesn’t militarily defend Ukraine, then why would China worry about, say, invading Taiwan, for instance?

Now, what people need to ask is whether a show of strength is worth the loss of life and resources (the “blood and treasure” that people like to talk about).

The best case scenario, should the U.S. get militarily involved, is that Russia would cave to the west’s demands, get out of Ukraine, and allow Ukraine the choice to enter NATO. Additionally, it would make the U.S. appear strong. The worst case would obviously be a nuclear exchange between the U.S. and Russia. The risk of massive loss of life would be significantly increased should the U.S. become militarily involved.

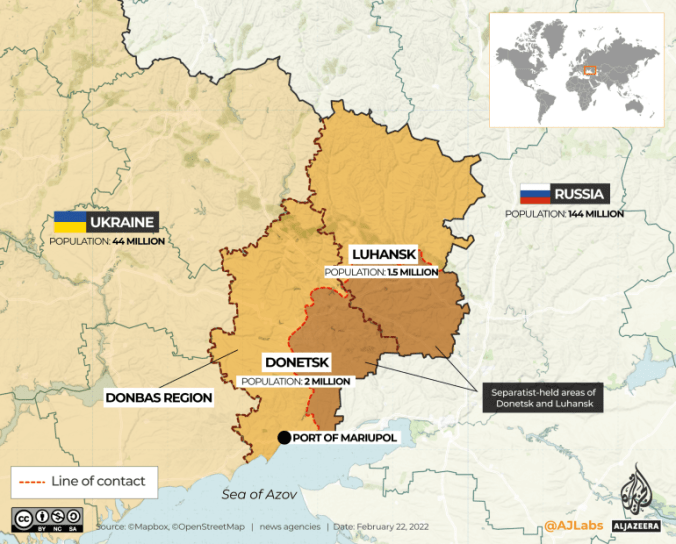

The best case scenario, should the U.S. not get militarily involved, is likely maintaining the (new) status quo. Luhansk and Donetsk would be “independent” (i.e. Russian puppet) republics. The worst case would be that Russia invades Ukraine and turns the entire country into a puppet state, possibly facing anti-Russian insurgencies. In either case, the U.S. would lose face, which other countries, such as China, might take as carte blanche to do what they want with their own foreign policy.

There is, of course, the very important and often overlooked question of what any of these choices would mean for Ukraine and the Ukrainian people. Becoming a Russian puppet state would be very undesirable for Ukraine, but so would be getting turned into a war zone (or a worse one that it already is). No matter what happens, Ukraine is the victim. In realpolitik, as Thucydides said, the weak suffer what they must.

My own view is, as usual, anti-interventionist. As much as I would like Russia not to invade Ukraine, and as much as I sympathize with the Ukrainians, who are the ones most affected by all this, I don’t think the U.S. should be getting involved in the conflict. I think if the U.S. gets militarily involved, it will have a high likelihood of only making things worse for everyone. That and after our poor performances in Iraq and Afghanistan, I just don’t have any confidence in our politicians and military leaders to prosecute a war very effectively. Regardless what ends up happening, this whole thing seems like an Alien vs. Predator situation: whoever wins… we (i.e. average people, especially the Ukrainians) lose.

—

I made a video based on this post: